alyaza [they/she]

internet gryphon. admin of Beehaw, mostly publicly interacting with people. nonbinary. they/she

- 2.13K Posts

- 1.01K Comments

3·5 days ago

3·5 days agoDuncan is an interesting guy these days. he is one of a number of Republicans who was basically run out of the party for refusing to be fascist and autocratic enough, and he was formally expelled from the party last year after endorsing Joe Biden and then Kamala Harris. i doubt he has sufficient distance or credibility to make it through a Democratic primary, but you never know. the Republican-to-Never Trumper-to-Democrat pipeline has been a pretty successful move for other people

3·13 days ago

3·13 days agofor more on this, see the New York Times article on the observatory: How Astronomers Will Deal With 60 Million Billion Bytes of Imagery

Each image taken by Rubin’s camera consists of 3.2 billion pixels that may contain previously undiscovered asteroids, dwarf planets, supernovas and galaxies. And each pixel records one of 65,536 shades of gray. That’s 6.4 billion bytes of information in just one picture. Ten of those images would contain roughly as much data as all of the words that The New York Times has published in print during its 173-year history. Rubin will capture about 1,000 images each night.

As the data from each image is quickly shuffled to the observatory’s computer servers, the telescope will pivot to the next patch of sky, taking a picture every 40 seconds or so.

It will do that over and over again almost nightly for a decade.

The final tally will total about 60 million billion bytes of image data. That is a “6” followed by 16 zeros: 60,000,000,000,000,000.

7·17 days ago

7·17 days agothe study: Majority support for global redistributive and climate policies

We study a key factor for implementing global policies: the support of citizens. The first piece of evidence is a global survey on 40,680 respondents from 20 high- and middle-income countries. It reveals substantial support for global climate policies and, in addition, for a global tax on the wealthiest aimed at financing low-income countries’ development. Surprisingly, even in wealthy nations that would bear the burden of such globally redistributive policies, majorities of citizens express support for them. To better understand public support for global policies in high-income countries, the main analysis of this Article is conducted with surveys among 8,000 respondents from France, Germany, Spain, the UK and the USA. The focus of the Western surveys is to study how respondents react to the key trade-off between the benefits and costs of globally redistributive climate policies. In our survey, respondents are made aware of the cost that the GCS [a global carbon price funding equal cash transfers] entails for their country’s people, that is, average Westerners would incur a net loss from the policy. Our main result is that the GCS is supported by three quarters of Europeans and more than half of Americans.

Overall, our results point to strong and genuine support for global climate and redistributive policies, as our experiments confirm the stated support found in direct questions. They contribute to a body of literature on attitudes towards climate policy, which confirms that climate policy is preferred at a global level17,18,19,20, where it is more effective and fair. While 3,354 economists supported a national carbon tax financing equal cash transfers in the Wall Street Journal21, numerous surveys have shown that public support for such policy is mixed22,23,24,25,26,27. Meanwhile, the GCS— the global version of this policy—is largely supported, despite higher costs in high-income countries. In the Discussion, we offer potential explanations that could reconcile the strong support for global policies with their lack of prominence in the public debate.

2·24 days ago

2·24 days agothis is going over hilariously on social media, despite the insistence by the Grammy’s that it has nothing to do with Beyonce’s win last year:

Recording Academy CEO Harvey Mason Jr. told Billboard that the proposal for the two new categories was submitted previously several times before it passed this year. The new categories “[make] country parallel with what’s happening in other genres,” he explained, pointing to the other genres which separate traditional and contemporary. “But it is also creating space for where this genre is going.”

Traditional country now focuses on “the more traditional sound structures of the country genre, including rhythm and singing style, lyrical content, as well as traditional country instrumentation such as acoustic guitar, steel guitar, fiddle, banjo, mandolin, piano, electric guitar, and live drums,” the 68th Grammys rulebook explains.

111·26 days ago

111·26 days agoi think this topic has about run its course in terms of productiveness, and has mostly devolved into people complaining about being held to (objectively correct) vegan ethics. locking

21·30 days ago

21·30 days agosomeone on Bluesky analogized what is happening to how QAnon transpired for most people, which is that the crazification it was causing simmered under the surface until January 6, when it all publicly exploded and the influence it had over a non-trivial block of the population became undeniable. hard to disagree with that!

15·1 month ago

15·1 month agothe paper in question: Efficient mRNA delivery to resting T cells to reverse HIV latency by Paula M. Cevaal et al.

1·1 month ago

1·1 month agodeleted by creator

27·1 month ago

27·1 month agojust a nightmarish headline. get these two the fuck out of here

192·1 month ago

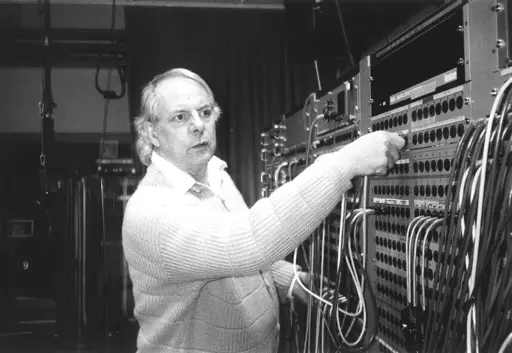

192·1 month agoArt rock legend Brian Eno has called on Microsoft to sever its ties with the government of Israel, saying the company’s provision of cloud and AI services to Israel’s Ministry of Defense “support a regime that is engaged in actions described by leading legal scholars and human rights organizations, the United Nations experts, and increasing numbers of governments from around the world, as genocidal.”

Eno’s connection with Microsoft goes back 30 years—he composed the famous boot-up jingle for Windows 95 that was recently inducted into the National Recording Registry at the US Library of Congress.

“I gladly took on the project as a creative challenge and enjoyed the interaction with my contacts at the company,” Eno wrote in an open letter posted to Instagram (via Stereogum). “I never would have believed that the same company could one day be implicated in the machinery of oppression and war.”

Regardless, Eno clearly isn’t interested in Microsoft’s protestations of innocence: “Selling and facilitating advanced AI and cloud services to a government engaged in systematic ethnic cleansing is not ‘business as usual’. It is complicity. If you knowingly build systems that can enable war crimes, you inevitably become complicit in those crimes.”

14·2 months ago

14·2 months agoand the press release from Fandom, which previously owned them for some reason:

San Francisco, CA - May 10, 2025 - Fandom, the world’s largest fan platform, is selling Giant Bomb to long-time Giant Bomb staff and gaming content creators Jeff Bakalar and Jeff Grubb. Financials of the deal were not disclosed. Giant Bomb’s programming, which was paused in order to work out the terms of this deal, will resume as quickly as possible. More details will be communicated soon by Giant Bomb’s new owners.

Statement from Fandom

“Fandom has made the strategic decision to transition Giant Bomb back to its independent roots and the brand has been acquired by longtime staff and content creators, Jeff Bakalar and Jeff Grubb, who will now own and operate the site independently. Fans are at the core of everything we do at Fandom and we’re committed to not only serving them but also supporting the creators they love, and the sale of Giant Bomb represents a natural extension of that mission. We’re confident Giant Bomb is in good hands and its legacy will live on with Jeff and Jeff.”

Joint Statement from Jeff Bakalar and Jeff Grubb

“Giant Bomb is now owned by the people who make Giant Bomb, and it would not have been possible without the speedy efforts of Fandom and our mutual agreement on what’s best for fans and creators. The future of Giant Bomb is now in the hands of our supporting community, who have always had our backs no matter what. We’ll have a lot more to say about what this looks like soon, but for now, everyone can trust that all the support we receive goes directly to this team.”

6·2 months ago

6·2 months agoadditional flavor text to this tense situation: Pakistan blamed a terrorist attack on India literally earlier today

13·2 months ago

13·2 months agoYou can post articles critical of the US, EU, Australian or any other government, but if you post a China-critical text you are whatabouted to death.

this will be a blunt comment. people would have no problem if you were doing this, but just in a quick scan, something like 10 of your last 15 submissions on our instance (Beehaw) are you obsessively posting about China–often from sources that are straight up fearmongering and/or guilty of doing literally the same thing they’re complaining China is doing. one of the most egregious submissions you’ve made in this vein is quite literally from the House Select Committee on China, as if the American government’s committee on “competition with the United States” doesn’t obviously have a vested interest in portraying things China does in the most uncharitable light possible (much as China would for America).

separately, and in a Beehaw context: at least from our userbase, you will largely not find disagreement that China is bad–nobody here really needs to be proselytized to the fact that China is an authoritarian capitalist country guilty of acts of imperialism against their neighbors, and probably of ethnic cleansing and genocide in Xinjiang. in fact, partially because of our political disagreements in that space, we do not federate with many of the Lemmy instances you might characterize as “pro-China.” this fact makes it incredibly conspicuous when someone like yourself obsessively posts every neurosis a Western country has about China on our instance. we’ve had a pattern of several users doing this in the past year or so–and at this point it’s blatantly propagandistic and Sinophobic bullshit we’re just not interested in letting people use our instance for.

even if you aren’t doing this for propagandistic reasons, though, and just think you need to push back against pro-China campists on Lemmy or whatever: this is also not your personal anti-China dumping ground, nor is it a place for you to shadowbox with campists who think China is cool. if you are genuinely posting in good faith: diversify your submissions and, if you don’t, at least drop the persecution complex when people push back on your voluminous China posting; if this is just using us as some middle-man in a bigger thing: going forward we’re going to aggressively prune these types of post.

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agodisagreement is fine, but both of you need to chill out a bit

6·2 months ago

6·2 months agoyou can find a May Day event here

11·2 months ago

11·2 months agothe website: https://onemillionchessboards.com/

Moderates

see also the Detroit Socialist article Airgas Teamsters on Strike in Ferndale: Greed Is in the Air