RedHat is making waves lately too, and they’re losing a lot of support from the open source community, which is where they really rose to prominence in the first place (can you say Fedora and Centos?) but while they should face a slight stumble over their final severing from the wider OSS community, they should do fine in the long term.

Hey, Relevant XKCD time!

The sky is blue. Why, you ask, is the sky blue? Because air is very very slightly blue.

You could ask why is air very very slightly blue, and the answer would have to do with Rayleigh Scattering, and probably some other effects.

You’ll get a similar, but slightly different response with water. Water’s color mostly has to do with the absorption of certain frequencies of light, whereas air’s color has to do primarily with the deflection of certain frequencies of light, but at the end of the day, both substances interact with light in a way that preferentially funnels certain frequencies of light away from them (and towards the observer).

Now, why is this relevant?

Because “color” is a word we use to describe an experience, or perhaps an observation, rather than a physical property. It’s not “real” in an empirical sense, since what we’re experiencing or observing is light that reflected from the object, rather than some physical property of the object itself.

Now, that’s not to say that color is all made up; a red cube does, verifiably, emit photons around 650 nanometers in wavelength. A violet cube will emit photons around 400 nm. Well, what wavelength does a magenta cube emit?

Trick question. It emits both 650 nm and 400 nm. It’s not a color on the visible light spectrum, it’s our brain’s interpretation of those two simultaneous signals.

So, while objects may absorb other frequencies of light, we describe their “color” by what they emit, or cause-to-be-deflected-into-our-eyes (depending upon the specifics of the mechanism, with Cherenkov Radiation being an extreme example).

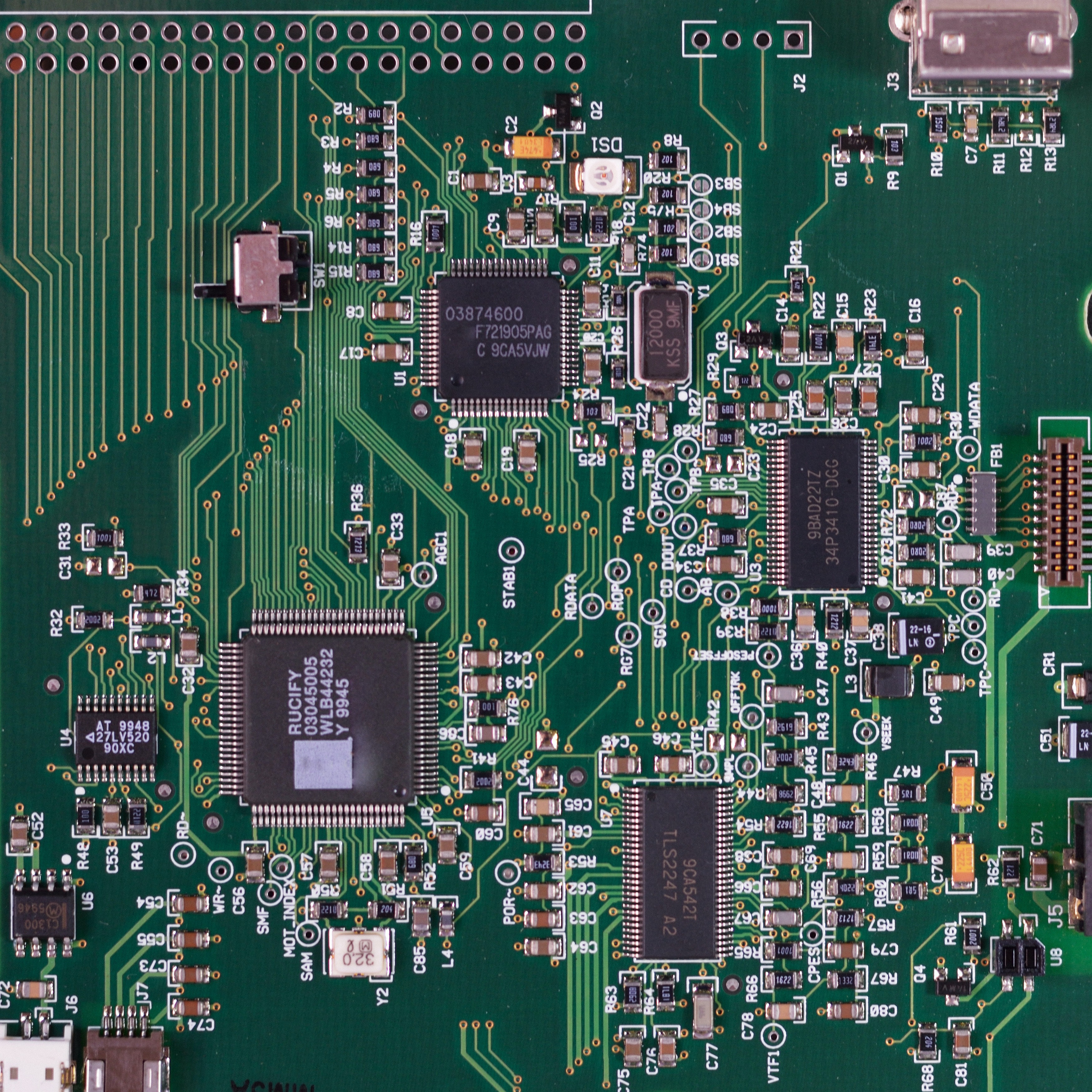

Now for the fun stuff. As discussed above, air is very slightly blue, but that’s only if your eyes can see blue. Just on the other edge of infrared from visible light is something called the Terahertz Gap. It’s an area of electromagnetic radiation that penetrates most of the materials we construct things out of (paper, wood, clothing, plastic, ceramic, etc), but is quickly absorbed by air. It’s very close to the frequencies used for millimeter wave scanning, like in airports. Because things like cardboard are invisible to it, it can be used in automated manufacturing processes to make a camera that inspects items coming off an assembly line after they’ve been packaged. This is especially helpful in electronics manufacturing, because you can photograph the inside of a computer chip.